From Architecture to Archaeology

Although Giuseppe Orefici devoted himself entirely to the recovery and preservation of Cahuachi at the beginning of the 1980s, as early as the 1970s he had already established ties with the Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici in Capo di Ponte, which offered doctoral degrees in archaeology:

“I dedicated myself to the study of rock art in Italy, France, and other places in Europe. I was fortunate to take part in the first archaeological mission to Algeria and Libya in 1979 and 1980, which opened up new horizons for me.”

He also worked for the Archaeological Superintendency, preparing reports on conservation and restoration projects in northern and southern Italy.

“In Lombardy, for example, we experimented with underwater archaeology (…) I always knew what I wanted, whether in art school, in architecture, or later in archaeology, always projecting myself in my own way: I didn’t work eight but fifteen hours a day, always trying to go further (…) From the beginning I published extensively in the archaeological field, which is very important to communicate and organize the information obtained and thus be able to move forward. Above all, my most important work was in Peru—forty consecutive years—but before or simultaneously I also carried out research in Cusco, in Madre de Dios, in Bolivia, Brazil, Chiapas (Mexico), Easter Island, Central America… all these experiences not only shaped me as an archaeologist but were also useful in discovering the differences required in approaching diverse cultures, always with the utmost humility, trying to understand as much as possible, and to recognize the uniqueness of each culture and each community.”

A Living Legacy in Cahuachi

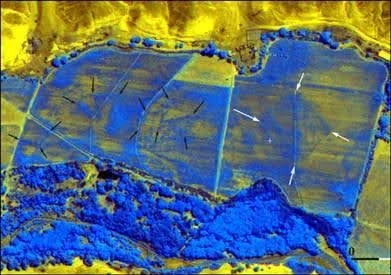

More than forty excavation seasons at Cahuachi, each representing one more step in uncovering the greatness of a civilization—a culture that proudly decorated the pampas with beautiful designs, monkeys, hummingbirds, spiders, and spirals, that channeled underground waters, crafted magnificent decorative and domestic ceramics, and built the gigantic citadel now reemerging on the face of the earth.

This effort is part of what can be considered a tradition: the Italian influence and presence—particularly of intellectuals and archaeologists—in Peruvian history and culture. Still, at a certain point, he had to choose…

How was it to move from architecture to archaeology?

“In Italy I worked on the restoration of monuments at least three to four hundred years old, or on Roman cemeteries, until I completely left my work as an architect—I couldn’t do both. I would be away for four or five months to live in Latin America (…) It was a problematic, complicated moment, really. I lived quite well as an architect, had very large projects, one on national building ownership, a studio with a colleague, and another on my own. We had many people working for us—draftsmen, foremen, supervisors, specialists. It was a good moment. But then I realized I couldn’t do both, because archaeology cannot be abandoned for two or three months. So I completely left architecture. From owning three cars I went down to a small one, and I had to reorganize my life in a completely different way.

As an architect, you have to win over clients and, in the end, do what they want. That was one of the reasons I left architecture: I didn’t want to be a slave to a client. I wanted to do, to the very end, what I could with my own hands—that’s for sure.”

But the decisive factor that made him choose archaeology was Cahuachi:

“Cahuachi became the most important thing to me. I was able to choose my collaborators and my friends, those who accompanied me for decades, especially Andrea Drusini, a physical anthropologist who worked with me in Venezuela, in Mexico, in almost all the projects I was involved in. We even took courses together in Wyoming (USA). He analyzed more than a thousand burials at Cahuachi. The same with Luigi Piacenza, a botanist. With them I built a warm and deep friendship, and likewise with many young Peruvians who started working with us at the age of 18. Some of them today hold important professional and academic positions in Peru at various levels.”

An Extraordinary Journey

His life has been anything but ordinary or sedentary, and a few brushstrokes show it: Giuseppe was in Managua when Fidel Castro arrived in that city; the permits he carried in his backpack were signed by Somoza, and the local coordinators of his visit had suddenly died shortly before. He worked in Chiapas at the height of the Zapatista movement, where the helicopters transporting the team of archaeologists and mountaineers still bore traces of the blood of those fallen in combat. The archaeological site was in tropical jungle, in caves suspended halfway up cliffs over a hundred meters high, which could only be reached by climbing. The rock paintings of Chiapas are of remarkable artistic beauty.

Giuseppe met some of the last surviving members of the Ese’Eja tribes in Madre de Dios. For decades, he spent eleven months a year in a tent in the pampas, a lunar-like landscape “where you depend only on your companions and an oil lamp.”

The camp was raided and looted in his presence around the mid-1980s. In Cahuachi, “I was taken hostage; they stole everything from us—things that can happen anywhere in the world.” In June 1992, supposed representatives of Sendero Luminoso arriving from Ayacucho sent him an ultimatum accusing him of being a “threat that needed to be eliminated.”

Neither this nor all the challenges of a recovery project such as Cahuachi managed to quell his drive for scientific research.

A Living Legacy in Cahuachi

More than forty excavation seasons at Cahuachi, each representing another step in uncovering the greatness of a civilization—a culture that proudly adorned the pampas with beautiful designs of monkeys, hummingbirds, spiders, and spirals; that channeled underground waters; that crafted marvelous decorative and domestic ceramics; and that built the gigantic citadel now reemerging on the face of the earth.

This effort forms part of what can be seen as a tradition: the Italian influence and presence—especially of intellectuals and archaeologists—in Peruvian history and culture.