First Encounter with Giuseppe Orefici

My first encounter with Giuseppe Orefici took place in Nasca in April 2007. We had previously exchanged a long series of emails in which I proposed using satellite imagery—an absolute novelty at the time—to identify buried sites and structures. Giuseppe was somewhat skeptical, yet curious. Upon my return to Italy, we planned the first mission, which also included geophysical investigations scheduled for August that same year. However, the earthquake of August 15 prevented the mission from taking place.

First Investigations and Initial Challenges

One of the greatest challenges was bringing back to Italy the geophysical instruments that had been shipped to customs on a cargo flight just days before the earthquake. Despite this setback, neither the earthquake nor customs issues diminished our enthusiasm. In April of the following year, we carried out the first CNR mission at Cahuachi. Under blistering heat and sometimes fierce winds, we worked feverishly to develop a modus operandi—a working method combining archaeology, geophysics, and satellite remote sensing to tackle a truly unique technological and scientific challenge: detecting adobe wall structures underground.

A Technological and Scientific Challenge

It was clear to us that the probability of detecting buried structures with ground-penetrating radar increased in proportion to the material differences between the structures and the covering soil. Detecting earth walls buried beneath earth was a real challenge. That very night, shortly after arriving—restless and feverish—I had strange dreams. I dreamt of Maxwell, the father of electromagnetism, and his equations, which in the dream were being invoked by a priest atop the Great Pyramid.

A Paradigm Shift in Research

The next day, we began scanning with ground-penetrating radar the areas scheduled for excavation. This allowed us to compare, in real time, the “geophysical scene,” made up of radargrams difficult to interpret, with the “archaeological scene.” Archaeology became functional to geophysics—a paradigm shift that worked.

Progress and Promising Results

Soon after, we developed a methodology for interpreting ground-penetrating radar, which we expanded to other geophysical techniques during a second mission in November. The results were excellent. The data collected, especially from the Orange Pyramid, proved extremely useful for excavation work on a ritual offering and numerous architectural elements brought to light by Giuseppe and his team. Enthusiasm was high. But the best was yet to come.

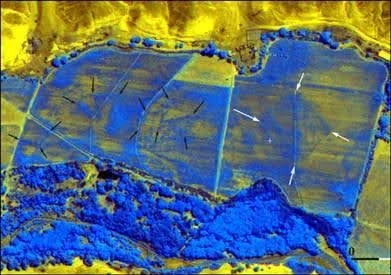

The Discovery of a Pyramid through Satellite Images

In December of the previous year, during Christmas holidays, I found myself almost by chance examining first Google Earth and later QuickBird satellite images of the Cahuachi pyramids and the Nasca Riverbed. I noticed that the paleochannels of the river were revealed by moisture variations and differential vegetation growth. Following these paleochannels, and while processing the images in false color with my wife Rosa Lasaponara—using specific spectral indices—I detected square-shaped traces. I discussed this with Giuseppe five months later, after a delicious dinner prepared by Nelly, the mission cook.

Confirmation of the Discovery

Giuseppe was impressed. “It could be a pyramid,” he said, “but let’s not rush.” The next day, with the help of a thermal camera, we carried out an inspection to verify what it was. It was indeed a pyramid. The results were presented at a conference in Rome. The news spread worldwide: newspapers, TV channels, and websites in the United States, Germany, Italy, and of course Peru covered the story. Thanks to satellite observation, Cahuachi was at the center of global attention.

The Nasca: Pioneers of Remote Sensing

We could not pay better tribute to the Nasca who, if we think about it, were truly pioneers of remote sensing—drawing geoglyphs on the arid pampas to be observed from afar or by the deities themselves. From that fortunate discovery of the pyramid, I began, together with Giuseppe, a more structured and interdisciplinary scientific project. This led us to broaden our research perspectives—no longer limited to detecting ritual offerings with ground-penetrating radar or buried settlements with remote sensing. Thanks to early applications with drones and geophysics, we began studying aqueducts, geoglyphs, and ceremonial architecture as interconnected parts of a cultural landscape.

Personal Reflections

More than fifteen years after our first meeting, I believe working with Giuseppe has been the luckiest thing that has ever happened to me. He is friendly, warm, and kind. In difficult moments, he supports you and helps you put problems into perspective. At the same time, he is never satisfied with what he has accomplished—what he does is never enough for him. He constantly seeks new challenges, always driven by the demon of dissatisfaction.

Author

Nicola Masini (1965), Italian scientist at the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), specialist in researching Andean civilizations in Peru and Bolivia through space technologies and remote sensing.